Nib

The nib has always been one of the most important parts of a fountain pen, and plays the final role of bringing the ink on paper. Fountain pens nibs derive from dipping nibs; the main difference is that being fountain pens much more expensive objects with their nibs continuously in contact with the ink, these were traditionally made of gold to have greater resistance to corrosion of the inks of the time (with different carats, although the most common remains the 14 carat, followed by the 18 carat).

When with the evolution of technology it became possible to create steel nibs resistant to corrosion, the biggest obstacle to their spread became that of marketing, and still today we tend to think of a pen with a gold nib as of higher value, although on the technical level this is probably lower. Gold, although strengthened by the metals added to the alloys used to produce nibs, is a very malleable metal, and for this reason a gold nib is subject to bend permanently much more easily than any steel nib and in general ends up being much less robust.

A "gold" nib, however, cannot be entirely composed of gold (ie 24 carats), as mentioned this material is extremely malleable, [1] so it is generally strengthened by mixing it as with other metals to obtain 14 carat alloys, which are the most common, or 18 carat, used to give greater value to the pen, but generally less robust. The ancient pens are however for the most part equipped with 14 carat gold nibs, the 18 carats have been introduced only where, as in France, an object with a lower carat could not be qualified as gold for legal reasons.

In the period of the second world war, however, with the restrictions caused by the war, the use of gold for nibs was greatly reduced and in some countries, such as Germany and Japan, even explicitly prohibited. At that time there was a flourishing of various steel alloys, often renamed, especially in Italy, with imaginative and high-sounding names, and experimentation with alternative materials, such as palladium, which now seem to be back in fashion. But the use of steel for nibs can certainly not originate from the constraints of war. In fact, it was adopted by some producers, in particular those oriented to the lower end of the market, well before the war and for simpler economic reasons. Even in that case, however, they often tried to "embellish" the metal with a gilding.

Regardless of the strength of the alloy used to produce it, a nib must still have a tip properly reinforced, as the wear would be excessive even for steel. The tip must rub for miles and miles on paper, and to have a durable nib it is produced using a much harder material. In this case the most common choice is that of an iridium alloy, and this is why often, to indicate the state of wear of the tip of a nib, reference is made to the amount of iridium present on it, although in reality this tip may have been made with other metals (for example another choice is that of osmium, or various combinations of both).

Usually the tip of the nib is made melting directly on place a ball of iridium (or equivalent material), and then it is cut in two dividing the tip in the two tines for the realization of the slit through which the ink coming from the feeder must pass, and then suitably polished to offer a better smoothness. In general then, both to allow the air to escape from the conductor and to reinforce the end of the slit, the nib is equipped with the so-called "air hole", even if in many cases the only purpose for it is to give a better mechanical strength and flexibility. Some nibs also, such as the Triumph Nib of the Sheaffer, or the central nib of the Omas 361, are specially designed and machined to write from both sides, including therefore also the so-called dry side.

The nibs are classified classically[2] based on a series of numbers expressing their size, although more or less all manufacturers have adopted similar figures (with values ranging from 00 to 12) the numbers do not have a reference to a precise measure, but are simply a relative indication (a nib #4 is usually larger than a #2 of the same manufacturer), and are different between a manufacturer and another. Very often, see for example the Waterman numbers and the Montblanc numbers, they were also used to identify the different models of a production line.

| Sigla | Dimensione |

|---|---|

| EF | Extra-fine |

| F | Fine |

| M | Medio |

| O | Medio-Obliquo |

| B | Largo (Broad) |

| BB | Doppia larghezza |

| BBB | Tripla Larghezza |

| OF | Obliquo fine |

| OB | Obliquo largo |

| OBB | Obliquo doppio |

| M | Musicale (Music nib) |

| KF | Kugel fine |

| KM | Kugel medio |

| KB | Kugel largo |

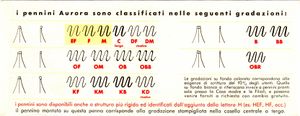

Another possible classification is that made on the basis of the size and possibly the shape of the tip of the nib itself (fine, medium, wide, etc..). Even in this case, there is no universal standardization adopted by all, even if many manufacturers have ended up using abbreviations that are quite uniform among them, such as those shown in the table on the right, most of which are still in use today.

Di nuovo si tratta di indicazioni relative, e non adottate da tutti (ad esempio la Waterman nel 1927 introdusse una classificazione basata su un codice di colori), per cui ci possono essere delle notevoli differenze fra pennini marcati allo stesso modo da aziende differenze; ad esempio per le diverse modalità di scrittura nei rispettivi paesi in genere un medio giapponese equivale ad un fine europeo.

Sempre nell'ambito della realizzazione della punta, oltre ai riferimenti alle dimensioni, sono state adottate delle nomenclature specifiche per indicare in maniera generica alcune versioni particolari di pennini, dotati di caratteristiche specifiche determinate appunto dalla forma della loro punta, per questa ulteriore classificazione si rimanda alle pagine del seguente elenco che li descrivono uno per uno:[3]

- pennino stub,

- pennino italico o pennino tagliato,

- pennino corsivo italico,

- pennino rotondo o kugel nib,

- pennino obliquo,

- pennino musicale.

Una terza possibile classificazione, ancora meno uniforme in quanto alla terminologia utilizzata, e che spesso non ha alcun riferimento ufficiale nella produzione delle varie aziende è quella relativa alla maggiore o minore flessibilità del pennino, una classificazione che inoltre tende a perdersi con la produzione moderna, dominata da pennini rigidi. Uno dei problemi delle stilografiche infatti (considerato uno svantaggio nei confronti della sfera, e quando risolto usato come fattore di promozione per le proprie penne) è quello che una pressione eccessiva sul pennino può nuocere allo stesso, cosa che rende abbastanza difficoltoso il ricalco.[4] Per questo una delle poche terminologie coerenti (almeno nel mondo anglosassone) è quella dei cosiddetti pennini da contabile (accountant nib), chiamati spesso anche Manifold, molto rigidi e duri, utilizzabili per questo anche per lavori contabili dove le copie a carta carbone erano la norma.

Non esistendo riguardo la flessibilità una terminologia ufficiale, (anche se alcune marche, come la Eversharp marcavano esplicitamente alcuni fra i propri pennini flessibili con la scritta Flexible) quella adottata nasce dalle convenzioni stabilite dai collezionisti, ed ha quindi anche un ampio margine di aleatorietà. Si è pertanto deciso, in maniera del tutto arbitraria, di fare riferimento alle seguenti definizioni:[5]

- molleggiato pennino che risponde alla pressione, ma senza creare una significativa variazione del tratto, molti pennini moderni dichiarati flessibili rientrano in questa categoria.

- demi-flex (semi-flessibile) pennino che risponde alla pressione con una significativa variazione del tratto, ma che usato normalmente non presenta variazioni significative.

- flexible (flessibile) pennino che produce una variazione di tratto anche nella normale scrittura, in risposta alle piccole variazioni di pressione in essa esercitate.

- wet noodle (super-flessibile) pennino estremamente flessibile, che deve essere usato con cura anche nella normale scrittura, portando a variazioni di tratto molto accentuate alla minima pressione.

Infine essendo un elemento essenziale della stilografica, il pennino ha conosciuto alcune variazioni costruttive da parte delle aziende. Inizialmente si è avuta una differenziazione portata avanti principalmente nei materiali costruttivi del corpo e della punta, ma fino agli anni '30 è sempre rimasto praticamente identico nelle forme e nelle funzioni. La prima significativa diversificazione è stata quella introdotta dalla Eversharp nel 1932, con il pennino a flessibilità variabile "Adjustable Point" dotato di una ghiera scorrevole. Ma i cambiamenti più significativi sono iniziati nel 1941, con l'uscita ufficiale sul mercato della Parker 51, che segnò il debutto del pennino carenato. Da allora si ebbero evoluzioni come il pennino conico della Triumph, le varie versioni di pennino alato dalla Wing-flow in poi, o il particolare "inlaid nib" introdotto con la PFM.

Note

- ↑ malleable (see [1]) is meaning a very soft material, easy to deform without losing its mechanical properties, in essence the exact opposite of strength and flexibility, gold is one of the most malleable materials that exist.

- ↑ by classically it is meant referring to the initial period of the spread of the fountain pen, this type of classification has now virtually disappeared.

- ↑ alcuni esempi di come si possano classificare le punte li trovate qui.

- ↑ oggi il problema non sussiste quasi più con la diffusione del digitale, ma non era banale quando le copie dovevano essere fatte a ricalco con la carta carbone.

- ↑ si è fatto riferimento alle definizioni di Davis Nishimura, come riportate in questo articolo pur non seguendole completamente.

Brevetti correlati

- Brevetto n° US-132008, del 1872-10-08, richiesto il 1872-10-08, di John A. Holland, John Holland Pen Company. Lega per i pennini.

- Brevetto n° US-269290, del 1882-12-19, richiesto il 1881-12-14, di John A. Holland, John Holland Pen Company. Pennino.

- Brevetto n° US-399306, del 1889-03-12, richiesto il 1888-03-16, di Paul E. Wirt, Wirt. Costruzione pennino.

- Brevetto n° US-763517, del 1904-06-28, richiesto il 1903-08-29, di Harry W. Stone, A. A. Waterman. Pennino.

- Brevetto n° US-772193, del 1904-10-11, richiesto il 1903-11-09, di De Witt C. Van Valer, A. A. Waterman. Costruzione pennino.

- Brevetto n° FR-360837, del 1906-05-04, richiesto il 1905-12-11, Roeder. Pennino e alimentatore.

- Brevetto n° GB-190708313, del 1907-12-31, richiesto il 1907-04-10, di Duncan Cameron, Cameron. Pennino Waverley per stilografica.

- Brevetto n° GB-190809818, del 1909-01-21, richiesto il 1908-05-06, di Duncan Cameron, Cameron. Alimentazione per pennino Waverley.

- Brevetto n° FR-396527, del 1909-04-14, richiesto il 1908-05-06, di Duncan Cameron, Cameron. Pennino Waverley.

- Brevetto n° GB-190828493, del 1909-08-19, richiesto il 1907-04-10, di Duncan Cameron, Cameron. Pennino Waverley per stilografica.

- Brevetto n° US-940509, del 1909-11-16, richiesto il 1908-11-28, di Duncan Cameron, Cameron. Pennino Waverley.

- Brevetto n° US-1154498, del 1915-09-21, richiesto il 1915-04-08, di William I. Ferris, Waterman. Lavorazione pennino.

- Brevetto n° GB-220793, del 1924-08-28, richiesto il 1923-06-27, di Theodor Kovacs, Günther Wagner - Pelikan. Pennino intercambiabile.

- Brevetto n° FR-582950, del 1924-12-31, richiesto il 1923-06-27, di Theodor Kovacs, Günther Wagner - Pelikan. Pennino intercambiabile.

- Brevetto n° DE-411787, del 1925-04-02, richiesto il 1923-06-27, di Theodor Kovacs, Günther Wagner - Pelikan. Pennino intercambiabile.

- Brevetto n° US-1613811, del 1927-01-11, richiesto il 1924-05-02, di Charles J. Funk, Wahl Eversharp. Lavorazione pennino.

- Brevetto n° US-1613812, del 1927-01-11, richiesto il 1924-06-11, di John C. Wahl, Wahl Eversharp. Lavorazione pennino.

- Brevetto n° US-1735199, del 1929-11-12, richiesto il 1924-08-14, di Charles J. Funk, Wahl Eversharp. Pennino intercambiabile.

- Brevetto n° US-1735224, del 1929-11-12, richiesto il 1924-09-13, di John C. Wahl, Wahl Eversharp. Pennino intercambiabile.

- Brevetto n° US-1779836, del 1930-10-28, richiesto il 1926-01-28, di John C. Wahl, Wahl Eversharp. Pennino intercambiabile.

- Brevetto n° US-1787406, del 1930-12-30, richiesto il 1926-08-12, di Donald D. Mungen, Robert Back, Wahl Eversharp. Pennino intercambiabile.

- Brevetto n° US-1800425, del 1931-04-14, richiesto il 1927-10-26, di Leon H. Ashmore, Esterbrook. Pennino piatto.

- Brevetto n° GB-373123, del 1932-05-17, richiesto il 1931-01-16, di Arthur Gilbert, Mentmore. Pennino in acciaio.

- Brevetto n° US-1867932, del 1932-07-19, richiesto il 1927-04-13, di Carl W. Gronemann et al, Wahl Eversharp. Processo produttivo pennini.

- Brevetto n° FR-729691, del 1932-07-29, richiesto il 1931-01-16, di Arthur Gilbert, Mentmore. Pennino in acciaio.

- Brevetto n° US-1869950, del 1932-08-02, richiesto il 1931-08-10, di Harry E. Waldron, W. A. Sheaffer Pen Company. Pennino Feathertouch.

- Brevetto n° US-1882780, del 1932-10-18, richiesto il 1930-01-02, di Arthur O. Dahlberg, The Parker Pen Company. Montaggio pennino.

- Brevetto n° US-1885862, del 1932-11-01, richiesto il 1931-06-29, di Salomon M. Sager, Sager. Pennino e alimentatore.

- Brevetto n° US-1918239, del 1933-07-18, richiesto il 1931-12-24, di Leon H. Ashmore, Esterbrook. Pennino intercambiabile.

- Brevetto n° US-1939753, del 1933-12-19, richiesto il 1928-11-19, di Edward S. Wood, Esterbrook. Pennino intercambiabile.

- Brevetto n° GB-412610, del 1934-07-02, richiesto il 1932-12-30, di Edward S. Wood, Leon H. Ashmore, Esterbrook. Pennino intercambiabile.

- Brevetto n° US-1980159, del 1934-11-06, richiesto il 1933-01-23, di Robert Back, Wahl Eversharp. Pennino Adjustable Point.

- Brevetto n° GB-420064, del 1934-11-23, richiesto il 1934-08-31, di Mark Sydney Finburgh, Wyvern Fountain Pen Company. Montaggio pennino.

- Brevetto n° US-1989220, del 1935-01-29, richiesto il 1934-02-20, di Norman E. Weigel, Wearever. Costruzione pennino.

- Brevetto n° US-1999177, del 1935-04-30, richiesto il 1933-01-31, di Leon H. Ashmore, Esterbrook. Pennino intercambiabile.

- Brevetto n° US-2012722, del 1935-08-27, richiesto il 1934-03-10, di Henry Krause, Chilton. Pennino intercambiabile.

- Brevetto n° BE-410533, del 1935-08-31, richiesto il 1934-08-31, di Mark Sydney Finburgh, Wyvern Fountain Pen Company. Montaggio pennino.

- Brevetto n° US-2016106, del 1935-10-01, richiesto il 1932-07-14, di Arthur O. Dahlberg, The Parker Pen Company. Pennino intercambiabile.

- Brevetto n° US-2019734, del 1935-11-05, richiesto il 1934-12-08, di Salomon M. Sager, Sager. Pennino centrale.

- Brevetto n° FR-792631, del 1936-01-07, richiesto il 1934-08-31, di Mark Sydney Finburgh, Wyvern Fountain Pen Company. Montaggio pennino.

- Brevetto n° DE-645085, del 1937-05-21, richiesto il 1934-08-31, di Mark Sydney Finburgh, Wyvern Fountain Pen Company. Montaggio pennino.

- Brevetto n° US-2089449, del 1937-08-10, richiesto il 1935-05-06, di Milford G. Sypher, Chilton. Pennino alato Wing-flow.

- Brevetto n° US-2105049, del 1938-01-11, richiesto il 1935-10-19, di Arthur N. Lungren, Wahl Eversharp. Pennino Adjustable Point.

- Brevetto n° FR-850525, del 1939-12-19, richiesto il 1938-08-23, Stylomine. Pennino coperto.

- Brevetto n° US-2208460, del 1940-07-16, richiesto il 1938-02-21, di David Kahn, Mack Seyforth, Wearever. Costruzione pennino.

- Brevetto n° US-2228250, del 1941-01-14, richiesto il 1935-08-27, di Leon H. Ashmore, Esterbrook. Pennino economico.

- Brevetto n° DE-701860, del 1941-01-25, richiesto il 1934-08-14, di Ernst Rösler, Kaweco, Montblanc. Pennino anti-corrosione.

- Brevetto n° US-2254975, del 1941-09-02, richiesto il 1940-09-04, di Milton R. Pickus, The Parker Pen Company. Punta pennino.

- Brevetto n° US-2267147, del 1941-12-23, richiesto il 1939-11-13, di Marlin S. Baker, The Parker Pen Company. Pennino tubolare.

- Brevetto n° US-2289963, del 1942-07-14, richiesto il 1940-10-24, di Benjamin W. Hanle, Eagle. Pennino intercambiabile.

- Brevetto n° US-2316478, del 1943-04-13, richiesto il 1941-10-21, di Norman E. Weigel, Wearever. Costruzione punta pennino.

- Brevetto n° US-2328116, del 1943-08-31, richiesto il 1942-09-23, di Norman E. Weigel, Wearever. Pennino coperto.

- Brevetto n° US-2328580, del 1943-09-07, richiesto il 1941-12-19, di Milton R. Pickus, The Parker Pen Company. Lega per pennini.

- Brevetto n° US-2338947, del 1944-01-11, richiesto il 1941-11-29, di Theodor Kovacs, Günther Wagner - Pelikan. Pennino intercambiabile.

- Brevetto n° US-2375770, del 1945-05-15, richiesto il 1943-11-19, di Arthur O. Dahlberg, The Parker Pen Company. Pennino e alimentatore.

- Brevetto n° GB-569286, del 1945-05-16, richiesto il 1943-11-16, di Arthur E. Andrews, William F. Johnson, Mentmore. Pennino a tre fenditure.

- Brevetto n° US-2410423, del 1946-11-05, richiesto il 1944-10-14, di Thomas F. Brinson, Scripto. Alimentatore e pennino.

- Brevetto n° US-2422351, del 1947-06-17, richiesto il 1944-12-23, di Benjamin W. Hanle, Eagle. Pennino intercambiabile.

- Brevetto n° US-2430023, del 1947-11-04, richiesto il 1944-01-27, di Sydney E. Longmaid, Esterbrook. Pennino economico.

- Brevetto n° US-2431015, del 1947-11-18, richiesto il 1943-11-16, di Arthur E. Andrews, William F. Johnson, Mentmore. Pennino a tre fenditure.

- Brevetto n° US-2432112, del 1947-12-09, richiesto il 1945-04-12, di Charles K. Lovejoy, Moore Pen Company. Pennino e sezione Fingertip.

- Brevetto n° CH-266126, del 1948-10-22, richiesto il 1944-10-14, di Thomas F. Brinson, Scripto. Alimentatore e pennino.

- Brevetto n° FR-938710, del 1948-10-22, richiesto il 1944-10-14, di Thomas F. Brinson, Scripto. Alimentatore e pennino.

- Brevetto n° US-2483603, del 1949-10-04, richiesto il 1946-03-18, di Russell T. Wing, The Parker Pen Company. Pennino tubolare.

- Brevetto n° US-2489983, del 1949-11-29, richiesto il 1944-02-14, di Victor H. Severy, Scripto. Alimentatore e pennino carenato.

- Brevetto n° US-2548906, del 1951-04-17, richiesto il 1945-10-19, di John William Para, Wearever. Pennino intercambiabile.

- Brevetto n° FR-983319, del 1951-06-21, richiesto il 1948-03-18, di Armando Simoni, Officine Meccaniche Armando Simoni. Pennino Omas 361.

- Brevetto n° US-2565667, del 1951-08-28, richiesto il 1948-03-18, di Armando Simoni, Officine Meccaniche Armando Simoni. Pennino Omas 361.

- Brevetto n° GB-656673, del 1951-08-29, richiesto il 1948-09-27, di Edward Stephen Sears, Swan. Pennino intercambiabile.

- Brevetto n° DE-1631271U, del 1951-11-22, richiesto il 1951-05-18, Montblanc. Pennino.

- Brevetto n° GB-666508, del 1952-02-13, richiesto il 1948-03-18, di Armando Simoni, Officine Meccaniche Armando Simoni. Pennino Omas 361.

- Brevetto n° US-2598171, del 1952-05-27, richiesto il 1948-03-06, di Philip C. Hull, The Parker Pen Company. Pennino a taglio orizzontale.

- Brevetto n° DE-856273, del 1952-11-20, richiesto il 1950-09-11, di William F. Johnson, Mentmore. Pennino.

- Brevetto n° US-2645206, del 1953-07-14, richiesto il 1948-06-04, di David F. Mohns, The Parker Pen Company. Pennino tubolare.

- Brevetto n° FR-1042361, del 1953-10-30, richiesto il 1950-09-11, Mentmore. Pennino.

- Brevetto n° GB-729639, del 1955-05-11, richiesto il 1951-03-01, di Edward Stephen Sears, Swan. Pennino intercambiabile.

- Brevetto n° US-2811948, del 1957-11-05, richiesto il 1954-06-06, di David Kahn, Morris Levy, Wearever. Pennino intercambiabile.

- Brevetto n° FR-1156940, del 1958-05-22, richiesto il 1956-07-13, di Umberto Legnani, LUS. Pennino intercambiabile.

- Brevetto n° GB-807974, del 1959-01-28, richiesto il 1956-10-11, di Kenneth Buckingham Robinson, Stephens. Pennino.

- Brevetto n° US-2987044, del 1961-06-06, richiesto il 1955-06-18, di Donald H. Young, Waterman. Montaggio pennino CF.