Differenze tra le versioni di "Anatomia di una penna stilografica/en"

| Riga 20: | Riga 20: | ||

{{:Fermaglio/en}} | {{:Fermaglio/en}} | ||

== Case back == | == Case back == | ||

| − | {{: | + | {{:Fondello/en}} |

== Notes == | == Notes == | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

Versione delle 22:36, 16 dic 2018

The distinguishing characteristic of a fountain pen is to be a tool combining a nib with an ink reservoir in a single writing instrument thus allowing long writing sessions without being continually interrupted by the need to re-dip the nib in the ink.

The first real fountains pens appeared around the end of 1800, although there were several predecessors designed for the same purpose, all poorly functioning. The success in creating a reliable tool that combined an ink reservoir to a nib is often traced back to the introduction of the multichannel feeder by Lewis Edson Waterman in 1884. Actually at that time there were already several producers who had built working fountain pens, whose essential elements remain the same even today.

Some components are always present in every fountain pen: the combination of the nib and the feeder (the so called nib group), the section (the end of the pen that holds the nib and feeder), the body of the pen, which is or contains the ink reservoir, and the cap (absent only on so-called desk pens). The photos of these various parts have been collected in a series of galleries that can be reached starting from this page.

Nib

Il pennino (nib nel mondo anglosassone) è da sempre una delle parti più importanti di una stilografica, e svolge il compito finale di portare l'inchiostro sulla carta. I pennini da stilografica derivano da quelli da intinzione usati in precedenza con la cannuccia; la differenza principale è che essendo le stilografiche oggetti molto più costosi col pennino continuamente in contatto con l'inchiostro, questi vennero tradizionalmente realizzati in oro (con diverse carature, anche se la più comune resta quella a 14 carati, seguita da quella a 18) per avere una maggiore resistenza alla corrosione degli inchiostri dell'epoca.

Quando con l'evoluzione della tecnologia diventò possibile creare pennini di acciaio resistenti alla corrosione, il maggiore ostacolo alla loro diffusione divenne quello del marketing, e tutt'oggi infatti si tende a pensare ad una penna con pennino in oro come di valore superiore, nonostante che sul piano tecnico questo sia probabilmente inferiore. L'oro, sia pure irrobustito dai metalli aggiunti nelle leghe utilizzate per produrre pennini, è un metallo molto malleabile, e per questo un pennino d'oro è soggetto a piegarsi in modo permanente molto più facilmente di qualunque pennino in acciaio ed in generale finisce per l'essere nettamente meno robusto.

Un pennino "d'oro" comunque non può essere interamente composto d'oro (cioè a 24 carati); come accennato questo materiale è estremamente malleabile,[1] per cui in genere viene irrobustito mescolandolo come con altri metalli per ottenere leghe a 14 carati, che sono le più comuni, o a 18 carati, usate per dare maggiore preziosità alla penna, ma in genere meno robuste. Leghe a maggior contenuto sono presenti in alcune penne moderne (21 carati) e negli anni '70 in Giappone si è arrivati fino ai 23 carati.[2] Le penne antiche sono comunque per la maggior parte dotate di pennini in oro a 14 carati, i 18 carati sono stati introdotti solo dove, come in Francia, per motivi legali non si poteva qualificare come d'oro un oggetto con caratura inferiore a questa.

Nel periodo della seconda guerra mondiale però, con le ristrettezze causate dalle esigenze belliche, l'uso dell'oro per i pennini venne notevolmente ridotto ed in certi paesi, come la Germania ed il Giappone, anche esplicitamente vietato. In quel periodo si ebbe un fiorire di leghe di acciaio di vario tipo, spesso ribattezzate, specie in Italia, con nomi fantasiosi ed altisonanti, e la sperimentazione di materiali alternativi, come il palladio, che oggi sembrano tornati di moda. Ma l'uso dell'acciaio per i pennini non si può certo far originare dalle ristrettezze della guerra. Infatti esso venne adottato da alcuni produttori, in particolare quelli orientati alla fascia bassa del mercato, ben prima della guerra e per semplici motivi economici. Anche in quel caso però spesso si cercava di "impreziosire" il metallo con una doratura.

Indipendentemente dalla robustezza della lega utilizzata per produrlo, un pennino deve comunque avere una punta opportunamente rinforzata, in quanto l'usura sarebbe eccessiva anche per l'acciaio. La punta deve sfregare per chilometri e chilometri sulla carta, e per avere un pennino durevole questa viene prodotta utilizzando un materiale molto più duro. In questo caso la scelta più comune è quella di una lega di iridio, e questo è il motivo per cui spesso, per indicare lo stato di usura della punta di un pennino, si fa riferimento appunto alla quantità di iridio presente sullo stesso, anche se in realtà detta punta può essere stata realizzata anche con altri metalli (un'altra scelta è ad esempio quella dell'osmio o varie combinazioni di entrambi).

In genere la punta del pennino viene realizzata fondendo direttamente sul posto una pallina di iridio (o materiale equivalente), questa poi viene tagliata in due dividendo la punta nelle due ali (tines), per la realizzazione del taglio (slit) attraverso cui deve passare l'inchiostro proveniente dall'alimentatore, necessario al funzionamento della stilografica, e levigata opportunamente per offrire una migliore scorrevolezza. In genere poi, sia per permettere la fuoriuscita dell'aria dal conduttore, che per rinforzare la parte terminale del taglio delle ali, il pennino viene dotato del cosiddetto foro di areazione, anche se in molti casi il solo scopo è quello di una maggiore robustezza meccanica e flessibilità. Alcuni pennini inoltre, come il Triumph Nib della Sheaffer, o il pennino centrale della Omas 361, sono appositamente progettati e lavorati per poter scrivere da entrambi i lati, compreso quindi anche il cosiddetto lato secco.

I pennini vengono classificati classicamente[3] in base ad una serie di numeri che ne esprimono le dimensioni, benché più o meno tutti i produttori abbiano adottato cifre simili (con valori che vanno dallo 00 al 12) i numeri non hanno un riferimento ad una precisa misura, ma sono semplicemente una indicazione relativa (un pennino #4 è in genere più grande di un #2 dello stesso produttore), e diversa fra un produttore e l'altro. Molto spesso (vedi ad esempio i numeri di Waterman e quelli di Montblanc) questi numeri venivano utilizzati anche per identificare i diversi modelli di una linea di produzione.

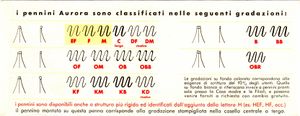

| Sigla | Dimensione |

|---|---|

| EF | Extra-fine |

| F | Fine |

| M | Medio |

| O | Medio-Obliquo |

| B | Largo (Broad) |

| BB | Doppia larghezza |

| BBB | Tripla Larghezza |

| OF | Obliquo fine |

| OB | Obliquo largo |

| OBB | Obliquo doppio |

| M | Musicale (Music nib) |

| KF | Kugel fine |

| KM | Kugel medio |

| KB | Kugel largo |

Un'altra possibile classificazione è invece quella effettuata sulla base della dimensione ed eventualmente la forma della punta del pennino stesso (fine, media, larga, ecc.). Anche in questo caso non esiste una standardizzazione universale adottata da tutti, anche se molti produttori hanno finito per utilizzare delle sigle abbastanza uniformi fra loro, come quelle riportate nella tabella a fianco, buona parte delle quali sono in uso ancora oggi.

Di nuovo si tratta di indicazioni relative, e non adottate da tutti (ad esempio la Waterman nel 1927 introdusse una classificazione basata su un codice di colori), per cui ci possono essere delle notevoli differenze fra pennini marcati allo stesso modo da aziende differenze; ad esempio per le diverse modalità di scrittura nei rispettivi paesi in genere un medio giapponese equivale ad un fine europeo.

Sempre nell'ambito della realizzazione della punta, oltre ai riferimenti alle dimensioni, sono state adottate delle nomenclature specifiche per indicare in maniera generica alcune versioni particolari di pennini, dotati di caratteristiche specifiche determinate appunto dalla forma della loro punta, per questa ulteriore classificazione si rimanda alle pagine del seguente elenco che li descrivono uno per uno:[4]

- pennino stub,

- pennino italico o pennino tagliato,

- pennino corsivo italico,

- pennino rotondo o kugel nib,

- pennino obliquo,

- pennino musicale.

Una terza possibile classificazione, ancora meno uniforme in quanto alla terminologia utilizzata, e che spesso non ha alcun riferimento ufficiale nella produzione delle varie aziende è quella relativa alla maggiore o minore flessibilità del pennino, una classificazione che inoltre tende a perdersi con la produzione moderna, dominata da pennini rigidi. Uno dei problemi delle stilografiche infatti (considerato uno svantaggio nei confronti della sfera, e quando risolto usato come fattore di promozione per le proprie penne) è quello che una pressione eccessiva sul pennino può nuocere allo stesso, cosa che rende abbastanza difficoltoso il ricalco.[5] Per questo una delle poche terminologie coerenti (almeno nel mondo anglosassone) è quella dei cosiddetti pennini da contabile (accountant nib), chiamati spesso anche Manifold, molto rigidi e duri, utilizzabili per questo anche per lavori contabili dove le copie a carta carbone erano la norma.

Non esistendo riguardo la flessibilità una terminologia ufficiale, (anche se alcune marche, come la Eversharp marcavano esplicitamente alcuni fra i propri pennini flessibili con la scritta Flexible) quella adottata nasce dalle convenzioni stabilite dai collezionisti, ed ha quindi anche un ampio margine di aleatorietà. Si è pertanto deciso, in maniera del tutto arbitraria, di fare riferimento alle seguenti definizioni:[6]

- molleggiato pennino che risponde alla pressione, ma senza creare una significativa variazione del tratto, molti pennini moderni dichiarati flessibili rientrano in questa categoria.

- demi-flex (semi-flessibile) pennino che risponde alla pressione con una significativa variazione del tratto, ma che usato normalmente non presenta variazioni significative.

- flexible (flessibile) pennino che produce una variazione di tratto anche nella normale scrittura, in risposta alle piccole variazioni di pressione in essa esercitate.

- wet noodle (super-flessibile) pennino estremamente flessibile, che deve essere usato con cura anche nella normale scrittura, portando a variazioni di tratto molto accentuate alla minima pressione.

Infine essendo un elemento essenziale della stilografica, il pennino ha conosciuto alcune variazioni costruttive da parte delle aziende. Inizialmente si è avuta una differenziazione portata avanti principalmente nei materiali costruttivi del corpo e della punta, ma fino agli anni '30 è sempre rimasto praticamente identico nelle forme e nelle funzioni. La prima significativa diversificazione è stata quella introdotta dalla Eversharp nel 1932, con il pennino a flessibilità variabile "Adjustable Point" dotato di una ghiera scorrevole. Ma i cambiamenti più significativi sono iniziati nel 1941, con l'uscita ufficiale sul mercato della Parker 51, che segnò il debutto del pennino carenato. Da allora si ebbero evoluzioni come il pennino conico della Triumph, le varie versioni di pennino alato dalla Wing-flow in poi, o il particolare "inlaid nib" introdotto con la PFM.

Feeder

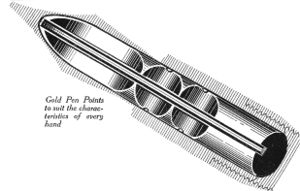

Although it is probably the least important part in the aesthetic aspect of a pen, the feeder (also called conductor or feed) is actually the heart of the working of a fountain pen, and on a technical level it is probably the most important component of it. It is in fact the feeder that creates the delicate balance of forces that allows the correct passage of the ink from the tank to the nib that deposits it on the sheet of paper, and a fountain pen writes well because its feeder does its job correctly.

The importance of this component is even more evident in the fact that the most important invention of Lewis Edson Waterman, the one that leads many to consider him (with some exaggeration) the father of the fountain pen, is related to the construction of the feeder. Of course, well before concentrating on materials and filling systems at the end of the 1800s, manufacturers were competing (and investing their research efforts) on this very element, which characterized their pens (think, for example, of Parker Lucky Curve or Waterman Spoon feed) since a well-functioning feeder was then what could lead to success or failure.

And although later on the importance of the feed, at least in the promotional material, has decreased at the expense of other parts and technical characteristics (and especially compared to the stylistic ones), it is still one of the essential parts of the functioning of a fountain pen, taken up in several cases by the manufacturers (as for the Eversharp Magic Feed or the Lamy tintomatic).

Apart from the still very primitive constructions present until the first years of 1900, which still provided for some companies (such as Swan and Onoto) the presence of the so-called overfeed the canonical shape of the feed as an element placed under the nib has been developing quite quickly.

Initially it was simply a cylinder of hard rubber suitably bevelled in the front part placed under the nib to leave space for writing, equipped on the upper part of the "channel" supply through which the ink arrives from the tank to the nib. The first variations occurred precisely in the construction of the channel, and in the addition of further grooves inside to facilitate the passage of the ink by capillarity. Through the same channel the air that replaces the ink that comes out of the pen tank flows (even if later possible alternative paths have been foreseen).

The first changes to the simple bevelled cylindrical shape occurred to solve the problem (then very pressing, but which still occurs today) to allow the blocking of the flow of ink when the pen is not used to prevent leakage in the cap. For this reason different solutions were adopted, with as many patents as the famous Lucky Curve of Parker, in which the rear part of the feeder was bent until it touched the wall of the tank, thus favoring (at least according to the claims of the project) the reabsorption of the ink.

Other solutions were produced for the same type of problem, such as the creation of appropriate side pockets next to the channel (as in the Spoon feed of Waterman). Over the years, the development of mechanisms has continued, either with the presence of engravings in more or less jagged shapes of the external part, as in the Parker Spear-head or in the variants of the comb feed created by August Eberstein (nº US-750271)) such as the Swan Ladder feed, or with the realization of fins, bags, engravings, channels and other configurations, to allow any excess ink to accumulate properly in the various folds, and avoid dangerous accumulations on the nib, in particular to compensate for pressure changes due to air in the tank, a problem that has become even more significant with the emergence of air travel. A photo gallery can be found on this page.

Section

It's called "section" the final block of the tip of the pen, the one in which the nib and feeder are inserted. The figure shows the three most common types of section present on antique pens, corresponding to three different types of filling system; for more details on this type please refer to the page on "section types and repair". A further nomenclature related to the section is that of the so-called "nipple", present only on some types of section (in the figure types 1 and 2), used on pens whose filling system requires the presence of a sac, which is usually glued on the collar.

The section is present on almost all the fountain pens except for some particular designs like PFM, where the nib is directly inlaid on the section and then protrude, or as in the Parker T1 or the Pilot Murex where the nib is the continuation of the metal body. To these specific exceptions are added all the safety, which for construction mode do not have a section, being the nib retractable inside the body of the pen.

The section, in addition to be used to keep in contact nib and feeder, is also the most common grip point of the pen in the writing phase, and for this it generally presents a flared part that allows a more secure grip. In some cases, as in the Parker 75, this is also suitably worked or shaped with ergonomic shapes (triangular, in the case cited) to offer specific support surfaces for the fingers that facilitate the handle.

Apart from this, the section is generally the part of the pen traditionally less subject in itself to innovations of a technical and stylistic nature, even if there are particular models that have some specific features such as the aforementioned Parker 75 with the ring for positioning the nib or the first series of Crest with the thread on the top of the section itself or the special sections with transparent window (the Visulated of the Sheaffer) used to make the ink level visible even with pens equipped with a loading system that generally does not allows it (as for example in the Balance and in the Doric with lever filler).

Barrel

The barrel, or body is usually the largest part of a fountain pen. In modern cartridge filled pens it has practically no other role than to provide support for the use of the pen and cover the cartridge, but initially, when the pens were loaded with droppers, it was used directly as an ink tank. This role is still played today with some filling systems such as the piston filler or plunger filler, in which case it is often equipped with transparent parts (windows or entire sections) to allow the display of the ink level.

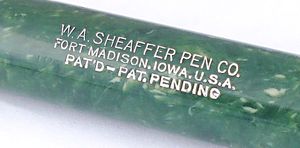

Even when the ink is not contained directly in the barrel, or in a part of it, but in a separate tank, as with all loading systems that use a rubber bag, the body still plays the role of container both for the latter and for the filling mechanism itself. Moreover, especially in the productions up to the '40s, it was typical to find the engravings of the brand and of the name of the producer (as well as of the possible patents of the pen).

Initially, also for the greater facility of working, it was realized in cylindrical form with flat ends (the so-called flat top) but following the evolution of the stylistic tendencies it has been passed to more tapered forms (with the birth of the so-called streamlined style). Moreover, with the evolution of stylistic trends from the ordinary round section, we have moved to multifaceted, triangular, square, octagonal, dodecagonal forms, etc.

In addition to differentiating itself for the various forms adopted by the producers, the barrel has also undergone the evolution in the use of the materials used in the construction of the fountain pens, of which it constitutes the largest component. At the dawn of the fountain pens it was mainly made of hard rubber like the rest of the pen, a material that guaranteed, having to serve as an ink tank, the necessary chemical resistance.

With the development of the technology all the other materials have been used then, starting from the metal (the first were probably the Wahl Metal Pen), the first artificial resins such as bakelite, galalith and celluloid, to pass in the '40s to the most common plastic resins still in use today. A photo gallery is on this page.

Cap

Apart from some particular designs (the Pullman of Météore, the Asterope of Aurora and the Capless of Pilot) the cap remains one of the essential components of a fountain pen. The cap basically performs two functions, on the one hand it provides the protection of the nib against accidental bumps to the outside, on the other hand it protects the outside from accidental contact with the nib (and especially with the ink brought by the same) and from any leaks. A photo gallery of different types of caps can be found here.

From a technical point of view, many inventions have been applied to the cap, almost always related to the way in which it can be opened or closed (interlocking, screw, snap, now also magnetic) and sometimes also to the way in which it can be inserted on the bottom of the pen to balance the weight or size of the same, as in the case of the Pilot Elite (but there are many precursors) in which for the use of the pen it was necessary to put the cap on it because this was a necessary extension of the body.

A second role played by the cap is to keep the environment around the nib well circumscribed, with the pen closed, so that the ink present on it does not dry out (causing a difficulty in restarting) on the one hand but does not even undergo pressure changes that can cause ink to escape. For this reason, there are both ventilated caps (with the presence of ventilation holes) and caps that are completely sealed. In particular, at the beginning of the 1900s, in order to guarantee against the loss of ink, the presence of a second inner cap began to be introduced as a constitutive part of many caps (significant patents nº US-764227 and nº US-1028382), which encloses the part on which the section is bent and isolates it from the rest of the cap, guaranteeing the seal of the ink. Sometimes this same element is also used as a locking component in the assembly of the clip, which can be mounted in a ring on the same, or wedged between the cap and inner cap by means of a lateral slot.

The cap is also often a characteristic element for the design and lines of a pen, and can be the subject of various decorations. Among these, a common element, widely used and still present on most of the caps, are the bands, or the various rings, whose original purpose was also strictly practical in nature. The edge of the cap is in fact one of the most stressed and subject to the risk of breaking a pen, and the original use of rings and metal bands (see patent nº US-662796) was precisely to reinforce the edge, and only later these have assumed the character of a decorative element.

Historically, the first caps were made with a friction closure (those that are generically defined slip caps), with the cap that fits on the body. There are different variants of this type of choice, depending on the way in which the joint is made; the two main classes are the so-called cone cap (conical section cap) in which the interlocking surface is a truncated cone, and the so-called straight cap (cylindrical section cap) in which the interlocking surface is cylindrical, among the latter there are then the so-called tapered cap (conical or tapered cap) in vogue at the end of the 19th century.

The interlocking caps which suffer, especially in the conical version, from problems of wear on the surfaces with loss of tightness, have been followed, with a trend established since the beginning of the '900, by the caps with screw closure (threaded cap), which are still among the most common today. A return of the interlocking caps took place in the '40s with the introduction of metal caps closed with friction on special rings (trend introduced by the Parker 51).

Towards the end of the 1940s, the first snap-action caps began to spread (one of the first companies to use them was the Matador with the Matador-Click model of 1949), which later became very common and still widely used. In this case, the quality of the mechanism is essential to ensure the long-term maintenance of the cap closure. A photo gallery can be found on this page.

Clip

Although the first fountain pens were not equipped with a clip and there are for example suitable pocket cases for the same (they are very typical of the Swan) the use of the clip (usually placed on the cap) has quickly established itself as an essential element to allow a simple attachment of the pen to the pocket of the shirt or jacket, becoming one of the most relevant components, present on the vast majority of pens.

In addition to the first older models, when the use of the clasp was not yet established, are generally an exception to its omnipresence pens for women, with a ring and chain to be worn as a necklace, or handbag pens to be kept in a pocket of the same, usually small size. Another exception are the desk pens, which do not use it being positioned in their housing on the base.

As for the other elements that make up a fountain pen, the clip became very soon a distinctive element of the pen, often going beyond its strict technical meaning to become a stylistic reference, such as the Parker arrow clip, still today a distinctive element of the company, or the shape that recalls the pelican beak used by the Pelikan. Not to mention indirect stylistic requirements, such as those imposed by the military regulations of the American army, which prohibiting the protrusion of the pen from the pocket have resulted in a particular conformation of the same.

But if in the history of the fountain pen the clip has distinguished itself mainly as a stylistic element, it has also played a not insignificant role on the technical level, starting from the various methods of assembling it (such as the washer mounting), or the measures to facilitate its introduction in the pocket (the Roller Clip of the Eversharp), to block the screwing of the cap (the Lox-Top of the Chilton) or to block the clip on the jacket (the hook clip of the Novum). A photo gallery can be found on this page.

Case back

Although it is not as widespread and common as the other elements dealt with so far, many models have, usually associated with their loading mechanism, a case back that covers the rear part (in relation to the nib) of the body of the pen. This element is not always present, as for many pens the back end is simply part of the shaft of the pen. A photo gallery of different types of knobs can be found here.

In many cases, a case back is only present for aesthetic and decorative reasons and may in turn contain specific decorations or inscriptions, such as the model number, but it is fixed. In other cases it is used to cover the access to the filling system (it is common in button fillers) and can be detached, usually by unscrewing it to access the mechanism, but in this case it has to be more properly called blind cap. Finally, the case back can be a direct part of the filling system itself (for filler such as the piston filler or the plunger filler) in which it generally plays the role of the part of the mechanical device (and then is better called knob) on which to act to activate the filler.

Notes

- ↑ con malleabile (vedi la voce di Wikipedia) si intende un materiale molto morbido e facile da deformare senza perdere le sue proprietà meccaniche, in sostanza il contrario esatto di resistenza e flessibilità; l'oro è uno dei materiali più malleabili che esistano.

- ↑ ma non esiste, a parte le esigenze di marketing, nessuna ragione tecnica per spingersi a questi livelli, che comportano comunque leghe meno resistenti.

- ↑ per classicamente si intende facendo riferimento al periodo iniziale della diffusione della penna stilografica, questo tipo di classificazione oggi è praticamente scomparso.

- ↑ alcuni esempi di come si possano classificare le punte li trovate qui.

- ↑ oggi il problema non sussiste quasi più con la diffusione del digitale, ma non era banale quando le copie dovevano essere fatte a ricalco con la carta carbone.

- ↑ si è fatto riferimento alle definizioni di Davis Nishimura, come riportate in questo articolo pur non seguendole completamente.

External references

- [1] Article on nibs